His Finest Hour

(The Story of Dr. John W. Keller)

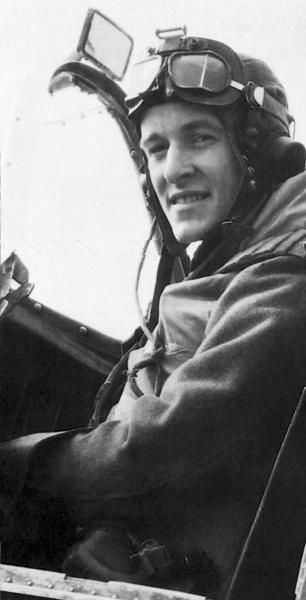

Few of the patients John W. Keller treated during his 38-year-long career in internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital would have suspected that his lifelong dream of becoming a physician took flight with the pinning on of a pilot’s wings.

During Keller’s senior year at Harvard College, England was losing the war, its Royal Air Force struggling valiantly to hold off Hitler’s Luftwaffe and delay the expected Nazi invasion. Keller found the contrast between the extravagant parties at Harvard and the suffering overseas unbearable. “By that time, two million Europeans, mostly Jews and forced laborers had died, and our newspapers every day showed the agony and bloodshed in England as hundreds of Nazi bombers visited English cities almost nightly. But there was denial—incredible denial—of what was occurring. America was divided, with great rallies in Madison Square Garden proclaiming isolationism and the vote to start conscription passing in Congress by only one vote!”

The spirit of isolationism extended to college campuses. A petition stating “Under no circumstance will I bear arms in defense of my country” was circulated in Harvard’s dining halls in 1940 and signed by nearly all undergraduates. “Far into the night,” Keller recalls, “I would argue with my classmates about the tragedy in Europe. My friends goaded me with, ‘If you are so sure Europe is in flames, why don’t you join up?’ So I did!” Unable to pay his way over to England, Keller joined the Royal Canadian Air Force under the Civilian Pilot Training program started by President Roosevelt. He began reporting regularly to Logan Airport, where he learned to fly in a tiny, 40-horsepower Piper Cub.

In Elementary Flying School in Canada, Keller learned to fly old biplanes called Fleet Finches. His instructor tied long red ribbons to the struts of his plane when he made his first solo flight. “I guess it was a warning for other planes to steer clear!” he notes wryly. He polished his training on Prince Edward Island, where he graduated to the powerful 450-horsepower planes called, ironically, Harvards. “The Good Lord was watching over me,” he says, recalling how he once lost control of his plane after a landing and knocked over a kerosene pot marking the end of the runway, spreading flames everywhere.

Near the end of his training, Keller received an offer to remain in Canada as an instructor but he was determined to join the action overseas. Three weeks before Pearl Harbor, Keller both earned his wings and got married. “The world seemed to be coming apart,” he says. “My wife, Patsy, and I just prayed that, if it broke in two, we might both end up on the same piece of it.” Three days after Pearl Harbor, he boarded the TSS Letitia, a converted hospital ship, out of Halifax for the two-week journey to Liverpool.

“The North Atlantic Ocean in December was an fearsome sight,” Keller remembers, “especially at night on the blacked-out deck in a convoy of 20 ships. The U-boats were at the height of their success, so we all wore life jackets during daily drills.” While Keller made the crossing, his wife headed home to Boston unaware that she was carrying their first child; Keller himself would not learn that he was to be a father for another five months.

When he arrived in England, Keller was told that no Hurricanes were available for training, as the fighter squadrons needed every last plane to defend against the daily Nazi raids. “Hurricanes,” Keller explains, “were the real workhorses that won the Battle of Britain, even more so than the more celebrated Spitfires.” To get his final flight training without delay, he boarded another troopship bound for the Middle East.

Keller was eventually ordered to report to No. 680 Squadron in Beirut, where he learned photographic reconnaissance in Hurricanes. In July 1943, he began flying missions on Spitfires traveling at 28,000 feet and 400 miles per hour while documenting the movement of Nazi troops and supplies below. Their Spitfires carried high-octane fuel in extra tanks inside their wings, enabling them to stay aloft for three or four hours at a time.

“On occasion,” Keller remembers, “the engine would just come to a complete stop at 28,000 feet—quite alarming, until one switched a few valves and restored the flow of gas to the Merlin engine.” He was later posted to Libya and ended up flying a total of 81 missions over Greece, Crete, and the Dodecanese Islands, for which he would later be honored with the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Keller had a number of close calls during his 81 missions. His plane was subjected to anti-aircraft fire on occasion from German 88-millimeter guns on the ground below; the bursts were inaudible above the noisy Merlin engine; only the tiny, blinking lights visible at the mouths of the guns signaled to Keller that he was being shot at. There were natural hazards as well. “On one occasion, I was returning from Greece at 28,000 feet when the Spit began to shake pretty violently. I barely maintained my altitude and headed for the nearest base. After landing, I switched off the engine and discovered that ice had thrown the wooden propeller off balance; a foot was missing off one blade, and two feet off a second of the four-bladed prop.”

Keller still has the bright red shirt he wore on ops. Each pilot in his squadron sat on a two-inch foam rubber pad covering a two-inch inflatable dinghy and a four-inch parachute; the red shirt was for maximum visibility should Keller end up in his dinghy in the mid-Mediterranean. Occasionally, this type of dinghy had been known to inflate accidentally, pushing the stick forward and sending the plane into a fatal dive. So, Keller carried a hunting knife in his flying boot to stab the dinghy if the need arose. His only other weapon was a flare gun for sending up a signal in case he ended up in the water. Yet, Keller says, “I was delighted to be flying the world’s best aircraft, the Spitfire, behind the best engine, the Rolls Royce Merlin, and in the world’s best airforce. We flew unarmed, unpressurized, and, for the most part, unafraid!”

But Keller keenly appreciated the dangers he survived. He was one of only four Harvard College men from his class to volunteer and one of only two to come home from the war. And Keller’s only brother, Russell, a naval officer, had been shot down and killed over Japan in 1945. When his service ended, Keller says, “I don’t think I have ever felt such joy as we headed home to Patsy, to my son Jeremy, to America, and back to life!” In his elation at arriving home, Keller left his full duffel bag leaning against one side of the car as he drove off from Boston’s North Station. All his possessions, including his logbook, were never to be seen  again.

again.

Keller was admitted to Harvard Medical School in September 1945, just after the war ended, a 24-year-old war veteran who was able to attend HMS in large part because of the Canadian equivalent of the GI Bill. He also relied on the generosity of his in-laws, with whom he and his family lived for the first two years of medical school. During his third year of medical school, the Keller’s moved to the third floor of a house in Chestnut Hill. They had to economize on everything, driving an ancient 1924 Model T Ford, brewing their own root beer, and even roasting rabbits that had been used for pregnancy testing at the Boston Lying-in Hospital. After his graduation from HMS, the hospital where Keller interned paid $24 a month plus room and board.

Yet Keller relished the postwar freedom and opportunities won with the sacrifices made by those who served and, in too many cases, lost their lives. “The moral of all this,” Keller insists, “is that extraordinary things can be done by ordinary people—and I was very ordinary.”

Published U.S. Legacies Jan 2003

- Log in to post comments